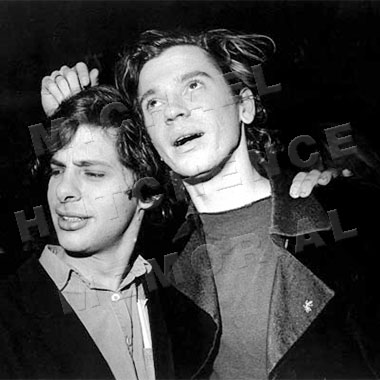

Richard Lowenstein and Michael Hutchence

What is your film about?

DOGS IN SPACE is an ensemble work that encapsulates an era that came about in the aftermath of the initial punk explosion in 1976. It is set in 1979 among the different sorts of characters that were around at that time – people from the post-punk and post-hippie era coming together.

How did you conceive this?

The script was written from a variety of people’s experiences. There was one household on particular in which there was a group of people very similar to the group in the film. The only thing I had to fictionalise was the character of Anna.

Over a period of three years, 1979–81, I tried to encapsulate events and incidents of groups of characters that seemed to sum up that ‘Who gives a fuck’ mentality. Then towards the end of the film you get a hint of what was to come out of that.

Could such a situation happen now?

Not in such a humorous form. I don’t think the contrasts are as strong as they were then, but I definitely think that sort of household can exist.

I think what is important to DOGS IN SPACE in the era we’re trying to re-create is the aftermath of the student militancy from the late 1960s and 1970s. That was very important because the punk generation in Australia came from the middle class. They were apathetic politically. At the same time there were the left-overs from the Vietnam moratorium days in the student unions running the campuses. They were very idealistic about socialism and unemployment and actually started to take on punk as an oppressed cry of the working class, which it might have been in England, but in Australia it was a total middle-class fashion.

People like Sam, Nick and Tim?

They are totally apolitical. Not rejected, but frustrated children from a middle-class background. A lot of them were like that, rejecting their parents, not having much to do with the family. It was really an art school punk crowd here. A lot of people used to look like dags or they might have bleached hair and that’s it. As far as anything political it would be totally the opposite. It would just be more apathy than anything else. But what went along with this was some interesting changes in music and independent recording.

What about the music then?

The music is very important because in the absence of anything political which the sixties had, the basic excitement was new music. It was a matter of getting rid of the rock dinosaurs and the guitar solos and introducing the synthesiser and the new style of music.

Bowie, Iggy Pop, Brian Eno, John Cale were all strong influences on the local music. Bands like The Boys Next Door and The Models started to have a lot of influence here. Society could not cope with that for very long. Slowly the mainstream recording companies caught on and most of the new music became assimilated into mainstream recording companies. Although diehards like Nick Cave and Ollie Olsen (Whirlywirld) resisted this.

Your refer to the ‘little bands’ in the film. Can you explain?

That was a thing that happened in 1980. People would congregate around other bands like Whirlywirld. It started off with 3 or 4 people getting together without rehearsing and getting up on stage to sing a couple of songs, cover versions or whatever. It began haphazardly and after a while got more established. Instead of having your support band you would have the major band like The Boys Next Door, and maybe ten little bands who would each play for ten minutes.

In the film we used four or five bands that classified a different style. We actually portray them with a lot more depth than they had at the time. The music sounded quite horrendous and a lot of the bands were just noise. We portray them as a bit more interesting than that.

The music in the film has been re-recorded hasn’t it?

Not all of it. All the live music in the film has been re-recorded and a lot of tracks are re-mixed versions of the originally recorded on tacky eight track machines. We had to find the original tapes and transfer them all onto 24 track and then mix them with all the latest gismo, which works quite well. We did mix a number of tracks of music from the era which is just background noise at parties and things like that but all the upfront music tends to be live. Anything that is live in the film tends to be old songs that have been re-recorded with live vocals sung over the top of them. We were actually recording the vocals on the day when we were shooting the scene which gave a very live feel to it.

It’s not mimed at all, so you get the added advantage if you want someone to start talking in the middle of a song or say something or shout, then that’s all on mike which gives you a greater sense of realism.

How did you go about casting for the film?

It’s very hard in this country to actually cast film like mine because you are looking for a fairly physical type as well as acting ability. In a place like America or London you have a vast number of people and faces, thin faces, sunken faces to choose from.

In Australia, if you go to casting agencies the range of people is fairly limited because it’s so hard to make a living as an actor.

When we started casting here it became obvious after a few weeks that we wouldn’t find anyone who was suitable from casting books to play Nick or some of the punks. Even Anna had to be someone who looked interesting and at the same time someone who didn’t look like she was out of the ‘Young Doctors’.

Also, we needed people who were very receptive to the lifestyle that we were portraying and trying to tell. This left us with no option except to go with people who had some interest in that era or lifestyle anyway. In a lot of cases we were really quite lucky with people, like Nique Needles for example, who had grown up in the era we describe and lived through it all. He had also played in one of the little bands. We tried to find as many of them as possible. We would comb the streets for interesting faces or people we thought could turn in a good performance, given a chance. We had a large cast remember, because of the nature of the film, sort of 10 major characters and another 15–20 supporting characters.

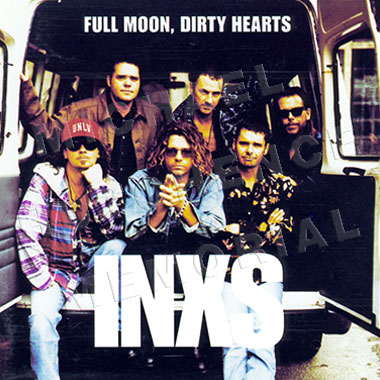

How did you come about choosing Michael Hutchence?

The initial idea for this developed around 1981. I remember Michael looked so similar to the main character in the film, Sam. The two characters also knew each other very well.

When the idea for the film was resurrected, it was done with Michael in mind. Then with getting to know Michael and with film clips that we made, observing him in everyday life and observing the way he acted and the way he told a story or told a joke or imitated people led me to believe that he could pull this off.

It was discussed with him before I started writing it as a script knowing that he would be willing to play Sam. So, it was really pretty obviously a part made for him.

Some of the cast are playing themselves aren’t they?

I did go with the actual people when the ageing process wasn’t too obvious. It was far easier for us to just go to the real character and say, “Well, you know the sort of character we’re talking about, just do it yourself.”

One of the difficulties was that a lot of the characters had mellowed quite dramatically in a few years. It was quite hard getting the people playing themselves to be as they were at the time. That created some difficulties.

We were trying to create the feeling of ten different things going on tat once which is what it was like. Very similar in style to ‘Hill Street Blues’ or ‘M.A.S.H.’. We tried to construct a shooting style of scenes but also the sound recording of the scenes. For instance, a kitchen scene where there are three conversations going simultaneously and they are all being recorded separately and you might be hearing them all simultaneously but you might be hearing grabs of of words, treating the dialogue not so much as integral to plot structure but as sound effects. So you are grabbing lines of conversation from different people. On their own they are not important but they do add to the atmosphere and the density of it all. The budget and the restrictions of the location kept it to a very simple shot structure with a lot of one shot scenes, a lot of moving cameras trying to link scenes and I think in most cases they were successful.

In editing, some of the one shot scenes were chopped up because we had character threads going through them. We had this opportunity to cross over between all the different elements.

You also filmed a lot at night and inside the house?

Probably not as much as I would have liked because many of the night scenes were shot during the day, like interiors. We shot a lot at night because of the realism of it all.

Some of the party scenes that we filmed in the day were hard to create. We had problems establishing atmosphere. It puts a lot of strain on you if you don’t shoot in as realistic a time frame as possible. So I tended to be very resistant to ‘Let’s shoot this day for night’ which is hell for the producer because with night time you have problems with money and everything.

Is there a history to films like DOGS IN SPACE in Australia or are we looking at a distinctively new style?

I think there have been a few attempts. Not really successful. There are obvious similarities between films like PURE SHIT and GOING DOWN, but nothing that has been structurally so adventurous. MONKEY GRIP had the potential to be very similar but I think it was destroyed in the filmmaking process. To make the thing work you must go back to the social document aspect of it. To make it believable it is very important that you treat it as factually as possible so you’ve got a given time and a given place and a feeling. You’ve got to actually put it into perspective to make it work. MONKEY GRIP was destroyed by taking a historical film and trying to put it into an early 80s punk era.

How do you expect DOGS IN SPACE to go overseas?

I think it will go quite well because it’s an universal situation. In England they started the whole punk thing and I know we will get some criticism that the punks are middle-class kids. But that is basically what the film is about.

But it has a very unique style. It’s not made in a bland, conventional manner. We have tried to do something quite different with the camera and sound. It has something for everyone. It should have a large appeal not just for young people, but people of all ages.

Casting the ‘hippie’ side of the fence was a big problem. We didn’t realise until we started how lost that fashion is. You think well, punk is coming in, new-wave black tights and dyed hair is in, but when you tried to find hippies that looked as they did in that era it was incredibly hard. People came in punked up because it was a punk film and we were looking for hippies. It’s hard explaining to someone who totally missed out on that in their early 20s. You say, ‘Forget everything, you’re in Queensland and you’ve done Nimin. They just look at you and say ‘What’s Nimbin?’ That was far harder than creating the punk roles I thought.

Where does ‘The Girl’ fit into the era?

Well, the young girl is the character that it all pivots around, an observer. I think to make something like that work you need to have an outsider, a symbol of sanity to make everything else work otherwise you become closely involved with the main characters and you think, ‘well, that’s the norm’. The young girl comes in as a quiet observer and gets caught up in it all. Getting towards the end of the film we tried to make it so that she begins to emulate the Anna character. At the end of the film she is left as the only person who continues on and there is a hint of a new generation that comes out of her experience. She really is our eyes in a way. She’s there as the observer and that’s why she is never given a name, just ‘The Girl’.

Why did you choose to film in a house and not in the studio?

It was quite important, as we had a lot of people who had not acted before, to put them in this house, to let them stay in there, in their own rooms, getting to know the directions of the place, get the feeling for the community of the house, begin to take on characteristics and begin to think that they are living what they are playing. It would have been a lot harder for them in a studio knowing they’re in a studio.

The other thing was the feel of the location which you can never get with a set. The feel of being able to see moving images out of the windows, seeing cars drive by. Being able to construct a scene which starts exterior and moves interior. This is rarely done these days in cinema.

It is part of the stylistic approach to have a fluid camera moving interior/exterior and giving you a firm idea of ‘this is next to that’ and ‘that is a real street out there’. We constructed a lot of one shot scenes that did start off outside and end up inside which is very hard to do unless you’re on location.

What sort of visual style did you have in mind?

In contrast to STRIKEBOUND, which was fairly dense, very edited, a lot of telephoto lenses and things, a montage style of film, I was going for a very sparse, wide angle feel to the film. I was trying to construct a film that was very much one shot scenes. I would only cut where I had to and would try to create not just one shot scenes around one theme or storyline, I would try and say, ‘O.K., we are going to do this in one shot but then try and crossover between 3 or 4 different elements in that one shot.’ So you might start off on one storyline and end up on another storyline or another couple of characters in the same shot.

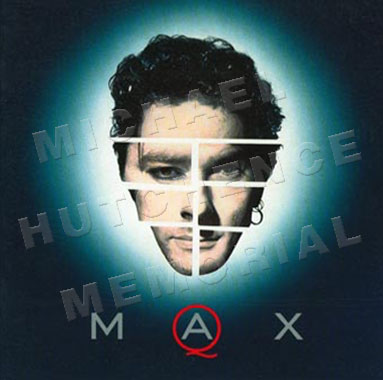

Before the release of the album the Australian master tapes were taken to New York City to be given a further polishing in the mix department by genius musical innovator Todd Terry from Chicago. A famous DJ who is one of the founding fathers of House music, Terry worked on the album and the attendant remixes (issued as b-sides and bonus tracks around the world). Michael and Ollie accompanied the movement of the music to NYC, and rooming together on the upper west side of town, finished the record and set plans and strategies into place for its release, promo and publicity.

Before the release of the album the Australian master tapes were taken to New York City to be given a further polishing in the mix department by genius musical innovator Todd Terry from Chicago. A famous DJ who is one of the founding fathers of House music, Terry worked on the album and the attendant remixes (issued as b-sides and bonus tracks around the world). Michael and Ollie accompanied the movement of the music to NYC, and rooming together on the upper west side of town, finished the record and set plans and strategies into place for its release, promo and publicity. In hindsight, Max Q proved to be a worthwhile side project that had a positive creative impact on INXS when they reconvened to record X in 1990, and future recordings throughout the next decade. One can hear the Max Q influence on INXS in songs such as ‘Faith In Each Other’, ‘Strange Desire’, ‘The Gift’ and ‘She Is Rising’. Interestingly, the b-side to the band’s very next single, ‘Suicide Blonde’ (after Max Q was released), a sassy track called ‘Everybody Wants U Tonight’ by Jon Farriss, bears a strong likeness to the Max Q material, showing that Michael was not the only one exploring new musical areas within the band at this time.

In hindsight, Max Q proved to be a worthwhile side project that had a positive creative impact on INXS when they reconvened to record X in 1990, and future recordings throughout the next decade. One can hear the Max Q influence on INXS in songs such as ‘Faith In Each Other’, ‘Strange Desire’, ‘The Gift’ and ‘She Is Rising’. Interestingly, the b-side to the band’s very next single, ‘Suicide Blonde’ (after Max Q was released), a sassy track called ‘Everybody Wants U Tonight’ by Jon Farriss, bears a strong likeness to the Max Q material, showing that Michael was not the only one exploring new musical areas within the band at this time. A must-have item in any comprehensive INXS collection, Max Q also connects in a very linear way with the Michael Hutchence solo album released in 1999 (U.S., 2000). Though Ollie Olsen is not part of that new album’s makeup, the style is similar in its assimilation of current left-field influences and odd recording approaches and performances. The biographical aspects of both records cannot be ignored either. ‘Possibilities’ from the posthumous solo album echoes sentiments of ‘Concrete’ from Max Q, and so on. In essence, Max Q was Michael’s first solo album, but to his credit he went to great lengths to establish it very much as a freestanding band apart from ‘Michael Hutchence of INXS,’ allowing for the project to stand or fall on its own merits.

A must-have item in any comprehensive INXS collection, Max Q also connects in a very linear way with the Michael Hutchence solo album released in 1999 (U.S., 2000). Though Ollie Olsen is not part of that new album’s makeup, the style is similar in its assimilation of current left-field influences and odd recording approaches and performances. The biographical aspects of both records cannot be ignored either. ‘Possibilities’ from the posthumous solo album echoes sentiments of ‘Concrete’ from Max Q, and so on. In essence, Max Q was Michael’s first solo album, but to his credit he went to great lengths to establish it very much as a freestanding band apart from ‘Michael Hutchence of INXS,’ allowing for the project to stand or fall on its own merits.